We all know it when we hear it. Great dialog practically leaps off the page. At its best, it’s a tantalizing tango between characters. It’s chock full of drama and tension, which leaves us nearly breathless and wanting more.

But writers who want to master their craft have to dig deeper and dissect conversations –much like specimens under a microscope. While studying the craft of writing, my instructors and other peers would sometimes comment that “nothing was happening” in a scene, even though I was convinced it was full of meaningful dialog. My conversations between two characters (usually women) was often a heart-to-heart talk about a relationship gone wrong. Here’s an example from a dozen years ago:

Ana: He keeps promising it’s going to be different this time.

Deb: (after a long pause) Do you believe him?

Ana: I don’t know.

Deb: Do you still love him?

Ana: (shrugs)

Deb: Well, I guess you have to think it over and decide how you feel.

Awful, isn’t it? At best, you can say that the dialog is lackluster and about as exciting as a grocery list. Finally, after writing hundreds of pages of miserable dialog, I admitted I needed help and turned to the experts. Following Robert McKee’s advice, I took a close look at one of my favorite movies, Casablanca, which revealed some of the secrets of powerful dialog.

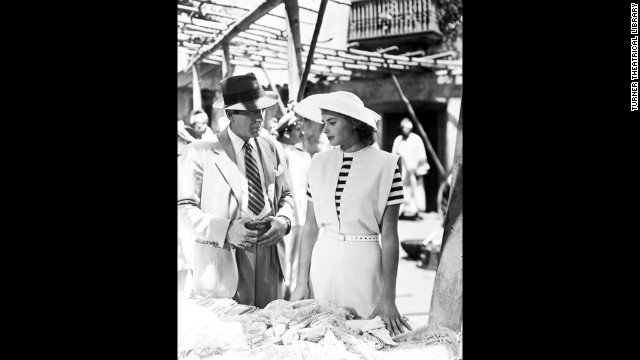

The bazaar scene from the movie “Casablanca.” Source: Google Images

Let’s examine one pivotal scene from the movie–when Ilsa meets Rick by chance at the bazaar in Casablanca. To set up the scene, here’s a little background. Ilsa and Rick were lovers in Paris right before the Nazi occupation. But on the day they were supposed to leave Paris together, she left him stranded at the train station with no explanation. Heartbroken, he has ended up in Casablanca, the last stop for many refugees from Nazi-occupied Europe. For years, he hasn’t seen or heard from Ilsa until she walks into his bar with her husband, Victor Laszlo, a famous Czech anti-fascist hero. Rick wants an apology from Ilsa–at the very least.

The scene opens with a conversation between Ilsa and the Arab linen merchant.

MERCHANT: (shows her a lace bed sheet) You’ll not find a treasure like this in all Morocco, Mademoiselle. (Holds up a sign reading 700 francs.) Only 700 francs.

RICK: (walks up behind them) You’re being cheated.

ILSA: It doesn’t matter, thank you.

MERCHANT: Ah…the lady is a friend of Rick’s? For friends of Rick we have a small discount. Seven hundred francs, did I say? (holds up a new sign) You can have it for 200.

Humor goes a long where here. Also a bit of mystery. When Ilsa says “It doesn’t matter, thank you…” is she talking to Rick or the Arab merchant? Or both of them? The mystery and humor continue:

RICK: I’m sorry I was in no condition to receive visitors when you called on me last night.

ILSA: It doesn’t matter.

MERCHANT: Ah! For special friends of Rick’s we have a special discount. (Holds up third sign—100 francs.)

RICK: Your story left me a little confused. Or maybe it was the bourbon.

MERCHANT: I have some tablecloths, some napkins…

ILSA: Thank you. I’m really not interested.

Again, we have the humor and Ilsa’s ambiguous comment “It doesn’t matter.” This is followed by the more pointed comment: “I’m not really interested.” We’re becoming more and more convinced that she’s talking to both the merchant and Rick. We also see that the conversation provides an opening for both Rick and Ilsa to explain their behavior and motivations–both past and present. But will they seize the opportunity? The scene continues:

MERCHANT: Only one moment…please…

RICK: Why’d you come back? To tell me why you ran out on me at the railway station?

ILSA: Yes.

RICK: Well, you can tell me now. I’m reasonably sober.

ILSA: I don’t think I will, Rick.

RICK: Why not? After all, I was stuck with the railroad ticket. I think I’m entitled to know.

ILSA: Last night I saw what has happened to you. The Rick I knew in Paris, I could tell him. He’d understand—but the Rick who looked at me with such hatred… I’ll be leaving Casablanca soon. We’ll never see each other again. We knew very little about each other when we were in love in Paris. If we leave it that way, maybe we’ll remember those days—not Casablanca—not last night—

RICK: Did you run out on me because you couldn’t take it? Because you knew what it would be like, hiding from the police, running away all the time?

ILSA: You can believe that if you want to.

RICK: Well, I’m not running away anymore. I’m settled now—above a saloon, it’s true—but walk up a flight. I’ll be expecting you.

In this segment, Rick offers his theory about why Ilsa left him at the train station–but she denies it. He ramps up the tension by propositioning Ilsa, but will she accept? Let’s read on. In the last few lines, she also drops her own bombshell:

(Ilsa turns away from Rick, her face shaded by her hat.)

RICK: All the same, some day you’ll lie to Laszlo—you’ll be there.

ILSA: No Rick. You see, Victor Laszlo is my husband. And was…even when I knew you in Paris. (Ilsa walks away from Rick, who can only stare at her in stunned silence.)

What can we learn from this masterful, short dialog?

- Dialog is not ordinary conversation. It doesn’t ramble. It’s compressed and focused, so it doesn’t have long pauses, meaningless aside comments, distractions, and a lot of fillers like “um…,” “ah,” “so” and “like.”

- Dialog serves several purposes—to advance the plot, reveal character, and create tension. In the snippet above, for example, we learn:

- Rick still loves Ilsa.

- Ilsa is married now and was married when she was Rick’s lover in Paris.

- Ilsa refutes Rick’s theory about why she left him in Paris.

- Rick has changed. Ilsa has no patience for the “new” Rick and not much respect for him.

- Rick lets Ilsa believe he isn’t involved any more in the resistance. But why?

You’ll notice that although the dialogue answers some questions, it also raises others. So, this leads to the next point:

3. Great dialog uses suspense. Structure the conversation so that it ends with a suspenseful punch. For example in the dialog, Ilsa’s bombshell–that she was married to Victor even when she and Rick were lovers comes at the end of the conversation. However, this revelation raises more questions, which will be resolved (we hope) in later scenes. So the lesson here is: keep some secrets until the climax of the scene and the climax of the book (or movie). In other words, don’t reveal all.

4. Great dialog doesn’t include long explanations about characters’ motivations. Imagine if Rick launched into a long explanation about why he was drunk the night before and why Ilsa should still love him. Or, if Ilsa explained in detail why she didn’t meet Rick at the train station. This leads to another key point: Motivation is revealed in action as well as in dialogue. Of the two, action is more effective.

5. Less is better. The more dialogue, the less effective it is. Cut unnecessary words and repetitive information.

6. Great dialog is all about conflict and confrontation. In real life, we may try to avoid strife and messy encounters, but they are key ingredients in fictional dialog. (By the way, this was often what was missing in most of my “early” attempts at writing dialog.)

7. Some idiosyncratic touches can enhance dialog. For example, you might use ethnic speech, favorite expressions and phrasing to reveal more about your character. Sol Stein, in his book Stein on Writing, provides an example from Woody Allen’s film, Bullets Over Broadway. Allen’s Italian-American character, Vitarelli, refers to Shakespeare’s play as “Ham-a-let” and a steak as a “sir-a-loin.” This advice comes with a warning: Do not to overuse these quirky elements or you will frustrate and bore your readers. Just small touches here and there will be enough.

All these insights have dramatically improved the dialogs I now write, making them stronger and more powerful. They are now effective tools in my writing “kit,” which I use to add tension and interest to a scene, help drive the plot forward, and reveal character.

For more information on writing effective dialog, I’d recommend Sol Stein’s Stein on Writing and Robert McKee’s Story. For writers, who would like some advanced techniques on writing suspenseful sentences, the website The Great Courses offers a terrific short course called “Building Great Sentences” by Professor Brooks Landon. The site has many special sales with significant discounts, so if you time it right, you can buy the course for under $50.00.

I loved it. Thanks for the great tips. Would you call ‘My Fair Lady’ a good example of nr 7? Thanks you very much.

LikeLike

You raise a great point, arthurdidymus! Given that the play Pygmalion was originally British, you’d expect that Eliza’s cockney accent would be authentic. But at the same time, it’s clear that later playwrights (Lerner and Lowe–I believe) made concessions for the British audience with a more “posh” and upper class dialect. That’s why Henry Higgins “translates” for Eliza at times! I’m also thinking of cases where an American writer creates a dialog with someone with a foreign accent. It would be very tedious if every word had to be deciphered. Here’s an example with an Italian speaker: “I’m-a-gonna tell-a you whadda I tink ’bout dat…” Can you imagine dozens of pages with that dialect???

LikeLike

I love number one – dialog is not regular conversation. It’s NOT, but it sure needs to sound like it. Can’t wait to check out the books you recommend. Great post! Thanks!

LikeLike

Good point, Randee. It has to sound like real conversation, but it’s not. I hope you find the books helpful!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on My world.

LikeLike

Hi Lindxey! Thanks for re-blogging my post! I appreciate it.–Patti

LikeLike

Thanks–excellent tips. Loved the example of the Casablanca scene.

LikeLike

Thanks so much, Michiko. I have learned so much from that movie!

LikeLike

These are terrific tips. I am a big fan of Casablanca, and the dialogue is brilliant. Another example of great dialogue that comes to mind is the film 12 Angry Men. The entire film is set in a jury deliberation room — one juror believes the defendant is innocent while the rest want a guilty verdict. Each juror’s words are direct, yet also laced with subtext. That film taught me a lot of good techniques for writing realistic dialogue.

LikeLike

Hi Jackie. Thanks! That movie is a great suggestion! I’ve heard wonderful things about it. I’ll put it on my list.

LikeLike

For me dialogue is the hardest part of fiction or non-fiction writing. I stay clear of it. Enjoyed this post.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on MAK5 Enterprise®.

LikeLike